As The Clearing’s Senior Manager for Technology and Digital Services, Chris Dietz identifies and deploys the right technology to support the firm’s strategic needs. As a former NYPD officer, Chris brings unique experience and insight to The Clearing’s work with federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies.

How is Data Currently Leveraged in Law Enforcement?

At a high level, there are two key ways data is used in law enforcement. The primary use is for investigative purposes. The secondary purpose is to better understand deployment and resourcing needs.

For investigations, data enables law enforcement to more quickly gather evidence than in the past. For example, investigators can now review data from license plate readers at the scene of a crime instead of relying solely on witness accounts; or review radiation data at the site of a bomb threat to more quickly secure an area.

When it comes to deploying resources, the use of data is a game-changer. Data allows law enforcement organizations to clearly delineate areas with high levels of criminal activity and deploy personnel accordingly.

At The Clearing, we work with federal law enforcement agencies. While the examples above apply, we also work with organizations on capturing and managing data as part of intelligence operations. This comes in the form of both cyber data and what agents call “pocket lint” – loose notes or seemingly unrelated information someone may have on them when they’re arrested. Accurately inputting and cataloging this collected information into a data management system helps law enforcement agencies connect the dots across their work.

How Does Data Improve Law Enforcement Agencies Effectiveness?

Data impacts all levels of law enforcement. However, I think the best illustration comes from local policing. I previously served as an NYPD police officer. While on the force, I used to hear stories from the 70s and 80s on how crime was tracked. There was an actual map of the precinct or the command on the wall and officers would put pins into the map where crimes were occurring. Juxtapose that with today, where you have real-time digital map visualizations. Combine that with data networks and mobile devices and we are now to the point where officers receive everything as it’s happening in real time. That means officers on patrol are more informed about the situation they’re going into and can better prepare for safe and optimal outcomes.

The other side of the sword is that the prevalence of data can be overwhelming and present ethical conundrums – for both local and state police and federal agencies. Imagine you’re a patrol officer in a squad car trying to drive, answer the radio, and look at a computer and a phone that are sending you constant updates. The answer is that as data systems evolve, we need to ensure the information being relayed to the field is both manageable and actionable and set expectations for officers accordingly.

For federal agencies, the sheer amount of data available requires the expertise to both understand it and use it effectively. There are also myriad legal, privacy, and ethical implications around some of the data captured by systems used by law enforcement.

In fact, the federal government has created a Data Ethics Framework to help federal employees, managers, and leaders make ethical decisions as they acquire, manage, and use data. At The Clearing, we work with federal Chief Data Officers to help them understand the implications of having this data and planning for how to use it effectively.

How is Law Enforcement Data Cleaned and What Opportunities Exist for Improvement in the Future?

First, let’s talk about what cleaning data means. Data cleaning is the process of finding and correcting corrupt or inaccurate records from a dataset. Basically, identifying incomplete, incorrect, inaccurate, or irrelevant parts of the data and then replacing, fixing, or eliminating it.

This is critical, as data is often freely captured and then stored in line with various department policies. For example, data is captured via license plate readers and then kept for three months or three years–whatever the case may be according to a given department. However, that type of data speaks to the privacy concerns I shared earlier. It requires leaders to determine how to collect, clean, and use that data ethically, not just capture everybody’s license plate that may be driving by and keep it in perpetuity.

Another area of critical importance when it comes to data cleanliness is facial recognition. In fact, Brookings recently published a paper on the disproportionate impact of facial recognition in surveillance and corresponding privacy concerns on communities of color. According to the paper, “Out of the approximately 42 federal agencies that employ law enforcement officers, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) discovered in 2021 that about 20, or half, used facial recognition.”

However, facial recognition software isn’t foolproof. This has led to a number of false arrests based on inaccurate data. One study cited in the Brookings paper highlights an analysis of three commercial facial recognition algorithms, finding that images of women with darker skin had misclassification rates of 20.8%-34.7%, compared to error rates of 0.0%-0.8% for men with lighter skin. This points to the critical importance of both effectively cleaning data and using it ethically.

When looking at the federal space, data cleaning is an area of concern. With the huge amount and variety of data points coming in, how does an agency effectively clean-up and make data readily available for analysis? Setting the correct strategy for collection, cleaning, and ethical use of data is critical to both ensuring they effectively leverage the information they capture and earning the public’s trust.

Is Law Enforcement Data Shared Nationally?

To a degree, a lot of law enforcement data is shared nationally; however, there is room for improvement. There are federal databases, like the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), that exist to collect law enforcement data from a variety of sources and distribute it to local, state, and federal entities. Then you have Fusion Centers. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security defines these as “state-owned and operated centers that serve as focal points in states and major urban areas for the receipt, analysis, gathering and sharing of threat-related information between State, Local, Tribal and Territorial (SLTT), federal and private sector partners.” In short, they’re a network of information hubs for sharing law enforcement data.

The risk at the federal level is that law enforcement agencies struggle to connect and collaborate with their investigative data because the standards that have been put together to outline how data systems are integrated with one another, how data is cleaned, and how it’s used aren’t well done.

Because of all the different systems in use, that means there is more of a struggle to integrate and share data at the federal level than we would like to see. In order to more effectively share and use data, we must explore government-wide policies instead of leaving those details to individual agencies.

How Can Agencies Use Data to Meet Future Demands?

We see law enforcement agencies across the board – federal, state, and local – struggling with budgets and personnel shortages. This makes the use of data even more important. As noted above, an agency can use crime hotspot data to more effectively deploy its personnel, helping overcome some shortages.

Data can also be used to evaluate personnel effectiveness and performance. I am a former New York City police officer; today I volunteer as a reserve officer in D.C.’s Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). At MPD, the department is using data to better understand how police officers are coping with the demands of their job. Here’s an example. Data allows department leadership to analyze personnel files and civilian complaints more effectively. What does it mean if Officer Sue and Officer John patrol the same area, but Sue gets lots of complaints while John doesn’t? By running that data through a multivariate regression analysis, we can more accurately determine if Sue is simply doing a bad job or if there are other factors at play.

Finally, law enforcement agencies are using data to better understand the overall wellness of their officers and agents. This includes tracking the impact of events law enforcement covers outside of what you typically imagine police doing. For example, crowd control at protests. Monitoring this data and officer response helps agencies anticipate trends and curb potential misconduct.

Taken together, these examples show how data will not only help agencies operate more effectively in the face of outside factors, but also facilitate better working environments for agents and officers while safeguarding the public.

What Else Should Leaders Keep Top of Mind?

I think there are two key takeaways for law enforcement leaders.

- First, don’t be afraid of data. While large amounts of information can be intimidating, developing a strategy to use it effectively can turbocharge your agency’s capacity.

- Second, ensure the strategy you develop and tools you use are ethically and technologically sound. There are few better ways to undermine trust in your agency than by inappropriately storing, misusing, or losing data in a breach.

Coming from a law enforcement background and now working in technology, this is a topic I’m passionate about. If you want to talk more about leveraging data at your agency or want to revamp your existing strategy, please reach out. I can be contacted at chris.dietz@dev2021.theclearing.com.

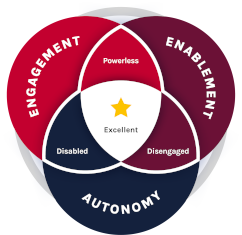

The Clearing’s Employee Experience

Improvement model, adapted from Itam

& Ghosh, 2020, focuses on three

objectives:

The Clearing’s Employee Experience

Improvement model, adapted from Itam

& Ghosh, 2020, focuses on three

objectives: